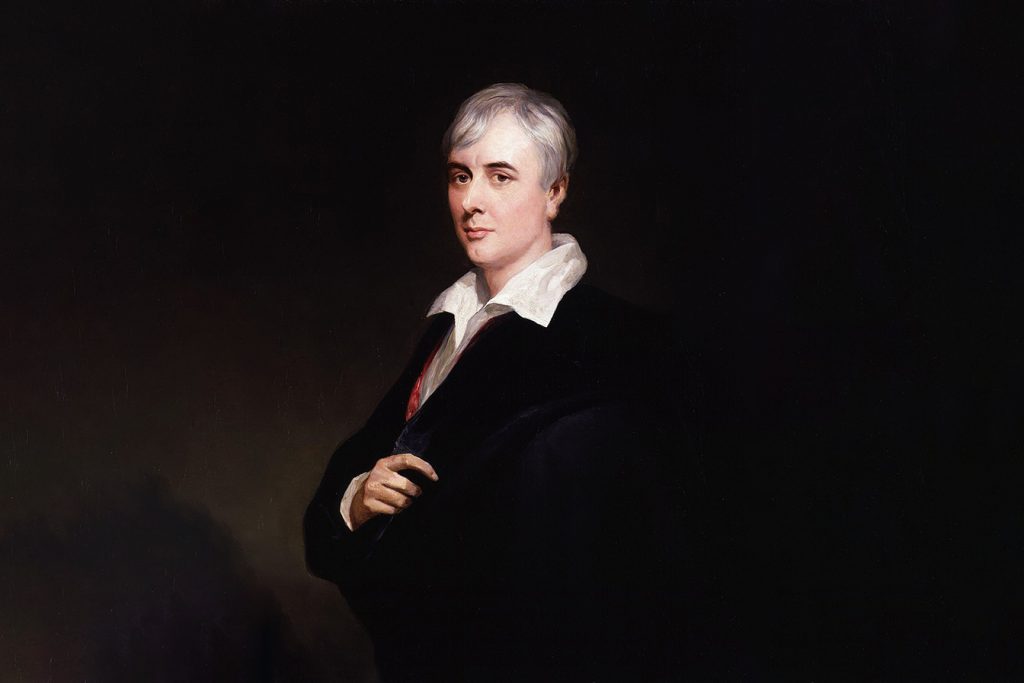

George Borrow: The Masterful Storyteller and the Art of Embellishment

Saturday, 2nd September 2023

Written by Gary

George Henry Borrow was born on July 5, 1803, in East Dereham, Norfolk, England. The son of a military man, Thomas Borrow, and his wife, Ann, George’s early life was marked by frequent relocations due to his father’s army postings. This nomadic upbringing, characterized by new towns and changing landscapes, perhaps sowed the seeds of Borrow’s later wanderlust and his affinity for the Romany way of life.

Borrow remains one of the most enigmatic and captivating figures in 19th-century British literature. A man of prodigious talents, his pen chronicled the lives and tales of the Romany people, painting vivid portraits that brought them into the living rooms of Victorian England. Yet, as with many great storytellers, the line between fiction and fact in Borrow’s writings often blurred, inviting both admiration and criticism.

The Landscape of Borrow’s Works

Borrow’s multifaceted background is evident in the breadth of his works. He was a linguist, traveller, and, most notably for our purposes, a writer. His two most celebrated books, “Lavengro” (1851) and its sequel “The Romany Rye” (1857), are semi-autobiographical, giving readers a glimpse into his adventures with Romany communities and his passion for languages. These works stand out for their rich, colourful depictions of Romany culture and the English countryside.

A Master of Narrative

There’s no denying that Borrow had a gift for narrative. He wrote with a vibrancy that made his characters spring to life, embodying the spirit and essence of the Romany. His storytelling prowess was such that he often transported readers to the very heart of the Gypsy camps, letting them almost hear the crackling fires and spirited discussions.

This capacity to weave tales made Borrow’s work popular in his time, offering Victorians an exotic escape from their daily lives. It also fostered a deeper curiosity about the Romany people, a community often marginalized and misunderstood.

Blurring the Lines: Fiction or Fact?

However, the very trait that made Borrow a masterful storyteller is also the source of contention. His tales’ vividness often came at the expense of factual accuracy. Scholars and critics have pointed out numerous instances where Borrow, sometimes inadvertently, sometimes purposely, embellished details or veered firmly into the realm of fiction.

One of the most renowned Romany characters in literature is Jasper Petulengro, first featured in “Lavengro”. While often believed to reflect the real-life Ambrose Smith, it’s essential to remember that Jasper is mostly a work of fiction. Intriguingly, the use of “Petulengro” (“Petul” meaning horseshoe, and “Engro” meaning man or thing – effectively “Blacksmith”) as a Romany equivalent to the surname “Smith” is first encountered in Borrow’s writings. Through his later work “Romano Lavo-lil” (1874), Borrow ensures that readers don’t easily forget this supposed “fact”.

However, the truth of the matter is that this interpretation (and the interpretation of many well-known Romany surnames) originated from Borrow himself. He ventured into a perilous realm by making such translations, blurring the lines between reality and fiction. What’s even more surprising is the persistence of this belief; many today still accept Borrow’s interpretations of Romany surnames as genuine, often unaware that these notions sprang from nothing more than Borrow’s vivid imagination and an overblown sense of self-worth.

many today still accept Borrow’s interpretations of Romany surnames as genuine, often unaware that these notions sprang from nothing more than Borrow’s vivid imagination and an overblown sense of self-worth.

Borrow claimed that the Romany community called him the “Romany Rye” or the Romany Gentleman. According to him, although initially seen as a foreigner to be wary of, they wholeheartedly embraced him once he conversed in their language. However, the veracity of this claim is questionable. It’s more plausible that Borrow’s acceptance within the community wasn’t entirely as he portrayed. Naming a book “The Romany Rye” after this supposed title further showcases Borrow’s audacity. It paints a picture of him as an integral part of the Romany community, assuming the authority to represent them, which he tries to do through numerous books. Such an act can only be described as the epitome of raw egotism, in this author’s humble opinion.

Borrow’s tendency to fabricate or exaggerate was not just limited to minor details. Some critics argue that entire works, notably “Romano Lavo-lil”, were more a product of Borrow’s imagination than actual fact. “Romano Lavo-lil”, effectively his dictionary of Romany words, is very much a blend of fact and fiction. While some of his translations are correct, others are purely fictitious, and the chapter regarding his translations and explanations of well-known Romany surnames can either be seen as pure narcissism by an amateur linguist who wanted others to view him as knowledgable on the subject or a joke at his expense, as told to him by some Romany fellow he met on one of his travels, who probably found it amusing to make fun of the gorger …

It’s essential to understand the context in which Borrow was writing. The 19th century was a period of great literary experimentation, with the lines between fiction, fact, and autobiography often intermingling. Borrow’s contemporaries, such as Charles Dickens, also used their works to illuminate societal issues whilst blending reality with artful fiction.

However, the ramifications of Borrow’s embellishments were significant. By romanticizing and sometimes misrepresenting Romany culture, he probably had no idea at the time of putting pen to paper just how much his work would contribute to forming stereotypes that still exist today. While his works introduced many to the beauty and richness of Romany traditions, they also inadvertently perpetuated certain myths.

The Legacy of George Borrow

Borrow’s legacy is a complex tapestry of masterful storytelling interwoven with contentious fabrications. While he undoubtedly put the Romany people on the literary map of England, his representations were not always accurate, leading to a skewed understanding that persisted for years.

His evocative and detailed accounts of Romany life and culture undoubtedly shaped the broader Victorian fascination with the Romany. While he was not a direct founder or active member of the Gypsy Lore Society, which was established later in 1888, his influence is palpable.

Borrow’s works, such as “Lavengro” and “The Romany Rye”, introduced a wide readership to the intricacies of Romany life, language, and traditions, thus laying a foundation of interest and curiosity. The Gypsy Lore Society, in its initial objectives to study and document Romany culture, language, and folklore, likely drew upon the interest kindled by authors like Borrow.

While the society had its academic and ethnographic aims, and its members might have approached the subject with different intentions than Borrow’s more romanticized accounts, the backdrop of enthusiasm and intrigue he created around Romany life can’t be easily dismissed.

George Borrow serves as a reminder of the responsibilities that come with storytelling, especially when depicting cultures and communities. While artistic license is a writer’s prerogative, it’s crucial to tread carefully to ensure that representation doesn’t slide into misrepresentation.

Article Copyright ©2023

Filed Under: Culture, Literature

Tags: Borrow, Lavengro, Romano Lavo-lil, Romany Rye, Smith

You Might Also Like To Read …

Archives

Tags

If you like what we do and want to support us, please consider making a secure Paypal donation (however big or small!) to help us continue this project ...